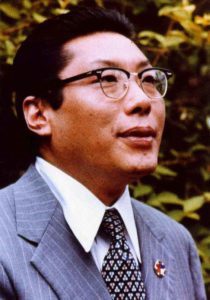

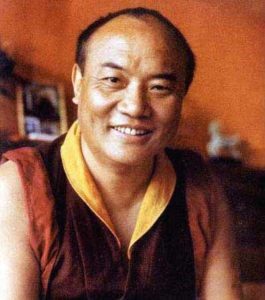

Choje Akong Tulku Rinpoche

Choje Akong Tulku Rinpoche

Vin Harris talks about the life of a remarkable man

I knew Akong Rinpoche as a friend and teacher for about forty years. Between 1978 and 1988, the Samye Ling community under his leadership built the first authentic Tibetan Buddhist temple in the West; it is named after Samye where Buddhism was first established in Tibet. Before his tragic death in 2013, work had started on a documentary film to tell the story of his life. After the shock of losing Rinpoche, it felt more difficult to continue with making the film, and at the same time it felt even more important to share his message of ‘compassion in action’ with as many people as possible.

So in late 2013, I joined the film team as Executive Producer to help bring the project to completion. The film, directed by Chico Dall’Inha, is called ‘Akong – a Remarkable Life’. It has already won several awards at international film festivals, and in March 2017 we had the official world première at Samye Ling.

Reincarnation and the Tulkus of Tibetan Buddhism

When he arrived in the UK in 1963, Akong Rinpoche’s passport showed his occupation as being “reincarnate Lama”. Within the Tibetan tradition, there is the possibility of lamas who have been of great service to their disciples and to their monastery consciously taking a new rebirth in order to continue their aspiration to help others; when that new reincarnation is found, it is recognised as a ‘Tulku’. One of the purposes of the film is to help us to understand the historical context in which Akong Rinpoche’s life was played out, and this requires some understanding of the notion of Tulkus.

The tradition of intentional incarnation began with the first Karmapa in the twelfth century. The film tells of many instances where Akong Rinpoche’s life was connected with both the 16th Karmapa who was his main guru, and the current 17th Karmapa who will be responsible for finding the next Akong Tulku. Two well-known lamas within Tibet leave predictions regarding the details of their own rebirth; one is the Dalai Lama, and the other is the Karmapa, who is the head of the Kagyu lineage to which Akong Rinpoche belongs. With most Kagyu lamas, the matter of finding their rebirth is normally put into the hands of the Karmapa or sometimes other lamas who are able to find these Tulkus; they will have a vision or a feeling of connection, and are able to describe the place of birth, the names of the parents and sometimes details like the colour of the door of the house. Then, when the time is right, they send out a search party to locate the young Tulku.

This all might seem to be quite a leap of faith for many people in the West; but it may not be so strange if we think of mind as never ceasing and of life as being endless. Perhaps if we see how we can become a product of our limiting habits, then we could envisage the possibility of being a manifestation of our positive intentions. The Tulkus’ intentions continue powerfully from life to life as the fruition of a commitment to help others. The Akong Rinpoche that we knew as a spiritual friend with great compassion and wisdom was considered to be the second incarnation of a line which has a particular connection with medicine, and he continued the association with healing as well as spiritual practice.

The second Akong Rinpoche was born in Dharak, in Kham in Eastern Tibet in 1939, and at the age of two, he was discovered by a party of people looking for the reincarnation of the first Akong, who had been Abbot of Drolma Lhakhang Monastery in Eastern Tibet. Quite often Tulkus are born to fairly poor people living in remote villages, and they regard it as a great honour to have a Tulku born in their family. However, they are taken off to the monastery at a very early age to be brought up by the monks, and the family is prepared to make this sacrifice for the greater good. Although Tulkus may have a very strong compassionate intention to be of use to humanity, they still need education and rigorous training so that they have the means to be able to truly benefit others.

In the case of Akong Rinpoche, his extensive training as a Tulku included religion and traditional Tibetan medicine, for which he and his predecessor were renowned. It also included experience of profound spiritual practice in isolated retreat. It is becoming apparent that one of the big challenges, as Tibetan Buddhism takes root in the West, is to establish the resources so that young Tulkus can receive this kind of traditional education, and so rekindle their abilities and fulfil their potential.

Escape from Tibet and arrival in the UK

In 1951 the Chinese invaded Tibet, and after the failed uprising in 1959, when Akong was just 20 years old, many of the monks felt that they had to flee the country to preserve the culture and lineages of the Tibetan Buddhist tradition. So Akong took the decision to leave, and set out with quite a large group of 300 people, led by himself and Trungpa Rinpoche, his childhood companion. They started with mules and horses and various possessions, but gradually all this dwindled until it was really just a matter of trying to survive. The Chinese army closed off all the usual routes, so they ended up walking through some of the most hazardous terrains, over mountains where there were not any tracks at all. They came very close to death, partly through encountering soldiers but also through lack of food. Akong Rinpoche used to talk of boiling up leather in water to just get some nourishment from it, and of living on water for weeks. In theend, only 13 of the group made it to India.

It is significant that even in these extreme conditions they refused to kill anything, because it is a Buddhist principle that all life has the same value. This great compassion was evident in Rinpoche even in these difficult circumstances, and it is something that I witnessed many times later in his life; he made no compromises to his core values. He told the story of when he was in a cave one night, at a time when they really thought they might die of starvation. In a moment of deep reflection he resolved that were he to survive, he wanted be able to help people: in particular, having experienced real hunger, he wanted to be able to feed people. This humanitarian aid was to become a major part of his work in later life. It was not initially in the foreground, but one day while we were building the temple at Samye Ling in the 1980s someone said to Akong Rinpoche: “What is it with you Tibetans? You spend all this money on gold, red paint, beautiful statues and this great big crystal chandelier, but what about helping people?” It is typical of Rinpoche that he thought about this, but rather than feeling that he had to make a choice, he said: “Well, why can’t I do both?” It was always like that; if you ever asked him: “Shall I do this or that?” he would reply: “Well, why can’t you do both?” This incident under the crystal chandelier in the temple was to be the birth of the Rokpa charity, which now works all over the world, feeding people and providing them with health care and education.

Returning to the account of the escape: they did eventually find a road out of Tibet across the Himalayas into a refugee camp in Northern India. What they found there was terrible; all sorts of diseases were rife and people were dying. Then they met an English woman called Freda Bedi, who was originally from Derby. She had an Indian husband, a Sikh called Baba Pyare Lal Bedi. She was living in India, working for the government and ended up being instrumental in helping many young Tibetan lamas, including the Dalai Lama. In later life, she actually became the first English woman to become a Buddhist nun. Her recently published biography entitled The Revolutionary Life of Freda Bedi: British Feminist, Indian Nationalist, Buddhist Nun is an account of another truly extraordinary life.

Freda Bedi seemed to connect particularly well with Akong Rinpoche and Trungpa Rinpoche. They ended up living in her house along with her own children, one of whom is Kabir Bedi who became a well-known Bollywood actor. She ran schools for the Tibetan refugees, and under the instruction of the 16th Karmapa, she set up the ‘Young Lamas Home School’ to train the monks and prepare them for their new life outside Tibet. The project flourished and she recruited Trungpa Rinpoche and Akong Rinpoche as her assistants.

One of the aims was to find jobs for the refugees, but Akong and Trungpa already had jobs: they were qualified as lamas! So she thought that if they could learn English, they would be able to continue their profession and things would work out well for them. Trungpa Rinpoche was very articulate and well-educated. Akong Rinpoche, although he had of course received a good education, was more inclined towards the way of showing by example and being active. So Freda Bedi obtained a scholarship from the University of Oxford for Trungpa Rinpoche, and the two young lamas were shipped across to England to start the next chapter of their amazing story.

The founding of Samye Ling

Once in Oxford, Trungpa studied at St Anthony’s College, and Akong worked as an orderly at the John Radcliffe Hospital to support them both. They were living in a small apartment with some other people. Lama Chime Tulku Rinpoche soon joined them, and slowly they made connections with the Oxford University Buddhist Society. A group of people interested in Buddhism grew up around them, and the idea came up of establishing something a bit more formal. So it was decided that they would start a centre where they could share their knowledge. Having investigated various possibilities, Akong Rinpoche and Trungpa Rinpoche were offered the chance to take over the Buddhist centre at Johnstone House in the Scottish Borders, and Samye Ling was founded in 1967. Lama Chime went on to set up a Buddhist centre at Marpa Housein Essex.

Akong and Trungpa Rinpoche had a very deep relationship. They were like brothers – dharma brothers. They were a similar age, had shared the same teachers, the same lineages, the same transmissions, and their monasteries were relatively close to each other. They were not from the same monastery, but they were not far apart and used to meet up to receive teachings from the same teachers. We might say of old friends “we go back a long way” but within the Tibetan tradition the lamas really do; they can go back many lifetimes. Trungpa was the 11th incarnation of his line, whereas Akong Rinpoche was only the second in his, so Akong Rinpoche tended to stay in the background, seeing his role as looking after Trungpa Rinpoche and facilitating his activity. John Maxwell, a retired judge, who is interviewed in the film, describes how he knew Akong Rinpoche for about ten years before he recognised his amazing qualities because he was so self-effacing.

So, at Samye Ling, initially the arrangement was that Trungpa Rinpoche was the teacher and Akong Rinpoche was the manager who looked after the practical issues. But after some time there was disagreement about how the dharma should be brought to the West. Some students have seen this as a big deal, but Akong Rinpoche never seemed to see it like that; it was nothing personal. His way was to be very cautious. The Tibetans have inherited the lineage of Buddha’s teachings and they know that it works. It is not always obvious why it works, or which bits work, so his view was that it would be wise to be careful to avoid ‘throwing out the baby with the bath water’. Akong Rinpoche was always very keen to stick closely to the tradition. Even now in Samye Ling we do not translate the Tibetan texts into English for the practices we do; we chant them in Tibetan because Akong explained that this carries the blessings of all the great lamas. He used to say that when a native English speaker becomes enlightened, then we can translate the texts into English with confidence!

Trungpa Rinpoche, on the other hand, was much more ready to engage freely with the West. He was very charismatic, very learned; he went on to write many wonderful books and they provide great clarity and insight into Buddhist teachings. He wanted to develop the traditional teachings and express them in modern terms. So there was disagreement regarding the approach to bringing Buddhism to the West. In 1970 it culminated in Trungpa leaving to teach the dharma in the USA, in which he was very successful. Even after Trungpa Rinpoche’s departure, Akong Rinpoche remained reluctant to teach and he used to invite other teachers to come to Samye Ling. It was not until the early ’70s that he started to give teachings himself and this was only because people asked His Holiness Karmapa to tell him to do so.

Once Akong Rinpoche had taken over responsibility for Samye Ling, things developed very slowly and gradually; he did not suddenly embark on new projects. Some of his ideas, like Tara Rokpa therapy, took almost 20 years to germinate. His first priority was to teach people the basics of Buddhism: the basic contemplations on the preciousness of human life, impermanence, karma and suffering. He instilled in us a great respect for the lineage, for the Buddha and his teachings. In the West we are so intelligent and well-educated that generally we want to go straight into the highest teachings. But Akong Rinpoche was always clear that we must start with the correct foundations if our practice is to have long-term benefit.

The students that Akong Rinpoche encountered at Samye Ling were very different from those he would have had in Tibet. The older generation were mostly ex-Gurdjieff people; they were cultured people but somewhat eccentric. The younger generation like myself were mostly hippies; we were quite unruly, although we did have positive aspirations. Akong Rinpoche talked to us and was willing to meet each of us where we were. Some of my friends really embraced the Buddhist path; they did long retreats and became monks and nuns. Others, like myself, became what in Tibet are called ‘householders’ – practitioners who have families and businesses. But Rinpoche was never judgemental; he did not try to make everyone the same, but helped us to develop within our own situation.

Akong Rinpoche invited many great teachers to bless Samye Ling, and he said many years later that he felt we had built a holy place because it had been visited by these teachers. Rinpoche always had a very clear sense that the most important thing was that Samye Ling should be a place where the Tibetan Buddhist dharma and Kagyu lineage would be preserved. However, it is worth keeping in mind that the ultimate purpose is not to preserve traditions for their own sake, but because they are of great value to a world which desperately needs to be reminded of the vital importance of kindness and compassion.

The three aspects of generosity

A big change came about at Samye Ling following a visit from the 16th Karmapa in the mid-1970s, when it was decided to embark upon the Samye Project – the building of a temple, a dining room, offices, college buildings and libraries, and so on. As always, Akong Rinpoche dealt with the most important things first and he decided to start with building the temple; so for a while Samye Ling had a temple which could hold 300 people but no additional bedrooms which could accommodate this number of visitors. The legend was that he had about £50 to his name when he began, but his teacher told him to build a temple, so he did.

This was the time when I became seriously involved. I was studying literature at Warwick University when I heard about Samye Ling. So I thought I would visit it for a couple of weeks and then go travelling. But Akong Rinpoche invited me to stay, as what used to be called ‘a house person’ – someone who looked after the house and the gardens and such like. We had a small herd of dairy cows, and so the first job I had after taking a degree in literature was milking cows, and making cheese and butter. Then I started doing building and maintenance jobs around the place.

When I was told by Akong Rinpoche about his project to build a temple, and that the plan was to build all of it ourselves, I had a kind of ‘road to Damascus’ moment. Ever since I was a child I had wanted to do woodwork, but because I showed academic ability at school I ended up on a conventional path of going to university. The moment I heard about the temple, it immediately seemed that the right thing to do was to offer to go away and learn woodwork in order to help with the project. Other friends went off to learn other skills, such as bricklaying, and after about a year we returned and started work. The first foundations were laid in 1978, and the temple was opened in 1988. Other parts of the complex – some of the café buildings and the retreat centre – were also built during this period, but the main focus was on the temple.

Accomplishing such a large task gave Rinpoche a degree of credibility. After that, people began to take him and his organisation more seriously. This did not seem to matter to him personally, but it was helpful in that it enabled him to fulfil his aspirations for Samye Ling. He often said that there were basically three main aspects to his work in the last period of his life. The first was the religious activities – the transmission of teachings at Samye Ling which I have already mentioned; the second was his humanitarian work through the Rokpa Foundation; and the third was the Tara Rokpa Therapy, which he developed as a way of helping people bring balance to their personal lives. This aspect of his activity was definitely linked to his role as a doctor and healer.

The charity Rokpa came about because of his association with Lea Wyler, a Swiss woman who is still President of the Board; she and her father initially sponsored projects and then helped Rinpoche to set up the organisation. Rokpa is mainly concerned with humanitarian aid to people in places which are difficult for other aid agencies to reach. Rokpa means ‘help’, and their motto is “helping where help is needed”. One of its main functions is to set up food kitchens, which Akong established in Tibet, Nepal, India and South Africa – as well as in the UK and Europe. One thing that he was very clear about was that he did not want the help to be conditional upon people converting to Buddhism: his concern was to address the common human needs that we all share. Another notable feature of his work was that it was never political: he never tried to fix the bigger problem, but would concentrate on people’s immediate needs, such as satisfying their hunger or providing them with health care and education. He never complained about the political arena in which he was operating, but concentrated on what he could do. This would often be rather puzzling and confusing for people, but the result was that his capacity to achieve what at first seemed impossible would continue to increase.

Tara Rokpa Therapy is a way of bringing the essence of the Buddhist dharma into another form, to the psychological realms – not as an intervention, but very slowly and very gently. One could say that it is perhaps even a way of bringing people to an acceptance of themselves so that they can start to engage with the Buddhist teachings. The attitude is not at all that there is something ‘wrong’ with people, and it is almost unfortunate that it is described as ‘therapy’. Most of us have need of this to some degree: I myself am involved in mindfulness teaching, and this also seems to me to be a way of getting to know ourselves a little better, learning to be compassionate towards ourselves, rather than taking on a spiritual path with the expectation that it will be a kind of magic formula to cure all our problems. As an American psychologist, Jack Engler, says: “You have to become somebody before you can become nobody”, and I think there is some truth in this. It is as if there is a twin track of self-transcendence and self-actualisation which need to work together. Without the process of self-actualisation, there is a tendency to skip round problems to the other side, and it is not enough. As Rinpoche said so many times: “We have to learn to face the situation”.

There is a synergy between the three areas of Akong Rinpoche’s religious, humanitarian and therapeutic activity. I regard each of them as acts of generosity. In Buddhism generosity is seen as having three aspects: giving dharma; giving food and shelter and the means of life – which is certainly what the Rokpa Foundation does; and giving freedom from fear. And it seems to me that the Tara Rokpa Therapy helps people to be less afraid in their own lives. In the end, the aim is always to bring people to a state in which they can recognise their own true nature. Rinpoche used to say: “You can’t teach people to meditate if they are hungry”, and perhaps hunger takes many different forms.

One of the sayings of Akong Rinpoche that has become famous is: “Only the impossible is worth doing”. He certainly demonstrated this in what he achieved during his life. Reflecting on the implications of it, I feel it is pointing to the heart of Buddhism – the illusory nature of a separate self. Rinpoche once summed up the matter up like this: “First of all there is me; then there is mine; then there is trouble.” So when he was pushing people – gently, but still asking them to go beyond their limitations – I believe that he was challenging the ‘me’ that says: “I can’t do that”. If you don’t go beyond your comfort zone, you are creating a safe place – a fortress – within which to exist. Another thing that he used to emphasise is that mind is endless – life is endless. You simply cannot think too much about the finishing line when you take on a really big project like the building of a temple. In fact, it is a very important understanding in Buddhism that we all have infinite potential. When taking on a large project you have to work with other people; we need to co-operate and admit that we need help, and we grow when we face difficulties and challenges.

Hope for the future

So, what now lies ahead for Samye Ling and the heritage that Akong left behind? In the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, the concept of the Tulku is enormously important: it is essentially the reassurance that there is continuity in the care given to people, as the Tibetan masters do not come back to the world for any reason other than to help others; they don’t come back for their personal agenda. For many centuries – millennia even – Tibet was a very stable society, and a young Tulku could be carefully educated there; there was always an older regent who was waiting for him to come of age and carry on the tradition. In the West, we are only just in the first generation of this process happening, and it is quite a challenge. I feel that Rinpoche set it up as well as he could do. His brother, Lama Yeshe, has been the abbot of Samye Ling for some years; so, although it was not easy by any means after Akong Rinpoche’s death, in terms of looking after Samye Ling, there was someone in charge. Lama Yeshe provided remarkable leadership by his example during this difficult period.

Now the 17th Karmapa has been asked to find the Tulku, the next reincarnation of Akong. His advice to us is that we should not worry about this but just carry on with compassionate activity as best we can. So we have tried to continue with the various projects that were already set up – and started some new ones as well.

Akong – a Remarkable Life

Over the last few years, it has been a privilege for me to help make this film about Akong Rinpoche’s life. It came about because my good friend Chico Dall’Inha, a Brazilian film director living in London, had the idea to make a film about Samye Ling. Then his plans evolved into a film about Akong Rinpoche’s life and, after some initial reluctance, Rinpoche gave Chico permission to go ahead. Fortunately filming was already in progress before he died, but in the shocking aftermath, it ground to a halt; apart from anything else, the funding had run out.

Then one morning I woke up just knowing how it could proceed. The vision that came to me was that people should see this film at special events: they should gather together and be inspired to carry on, as Karmapa said, with Rinpoche’s compassionate activity. It seems that when the idea is right, money is never a problem. So the thought came of asking Rinpoche’s many loyal friends to support us, which they did in so many different ways. So now the film is completed and thanks to everyone’s generosity, it has no debt. Any funds that are raised through its screening are donated to support the continuation of Rinpoche’s humanitarian work, and to support the education of the Tulku when he is found.

We specifically decided to organise the distribution of the film ourselves because this also feels consistent with Rinpoche’s direct and creative way of getting things done. Through engaging our network of connections, we already have more than sixty screening opportunities in more than fifteen countries. At every showing of the film, at least one person comes forward with an offer to set up another screening, and so the momentum builds as everyone is able to find inspiration and contribute to Akong Rinpoche’s legacy of compassion in action.

Vin Harris

Currently he is a Director of a successful joinery business specialising in traditional sash windows, as well as a founding board member and tutor of the Mindfulness Association, and an honorary teaching fellow on the University of Aberdeen M.Sc. in Mindfulness Studies. Vin takes on a wide range of inspiring projects, including helping to bring the film ‘Akong – a Remarkable Life’ to completion. One of his few regrets regarding this rich and varied life is that he does not get to play as much golf as he would like.

Image Sources:

Banner image: Akong Rinpoche at the inauguration of the shrine room at Samye Ling. Photograph by Chico Dall’inha.

Thumbnail image: Akong Rinpoche. Photograph by Gerry McCulloch. Darshanaphotoart.co.uk

Reference Sources:

Rinpoche, Akong Tulku, and Clive Holmes, Taming the Tiger:Tibetan Teachings for Improving Daily Life, (Rider, 1994).

Rinpoche, Akong Tulku, Restoring the Balance; Sharing Tibetan Wisdom, (Dzalendara Publishing, 2005).

Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, Cutting Through Spiritual Materialism, (Shambhala, revised edition 2010).

Chogyam Trungpa and Francesca Fremantle, The Tibetan Book of the Dead: Great Liberation through Hearing in the Bardo(Shambhala, new edition, 2000).

Vickie Mackenzie, The Revolutionary Life of Freda Bedi: British Feminist, Indian Nationalist, Buddhist Nun, by (Shambhala, 2017).

More information about the film Akong– A Remarkable Life can be found at http://www.akong-remarkablelife.com

For details of future screenings see http://www.facebook.com/AKONGaremarkablelife/

To organise a screening event, please email trust@hartknowe.org

Reprinted with the kind permission of the Beshara Trust.

[Special thanks to Vin Harris, Chico Dall’ignha and Jane Clark for their help in publishing this article in Many Roads for Bodhicharya. Apologies for any unsourced photographs appearing in the article. Albert Harris, Editor]

Leave a Reply