I receive an email from a friend, Tamuly Jung in France, telling me that a neighbour of hers, David Brazier, is in Edinburgh for events organised by the Edinburgh International Centre for Spirituality and Peace. This is an events-led Scottish charity organising programmes to promote the understanding of spirituality, and of interspirituality and intraspirituality, and its diversity. She tells me that he agrees to let me use excerpts from his latest book, Not Everything is Impermanent.

Dr David Brazier is the President of the International Zen Therapy Institute, Dharmavidya of the Amida Order of Pureland Buddhism, Zen master, psychotherapist and author of nine books. David resides a couple of villages distant from Tamuly who is living in a commune, The Oasis of Long Life. [See previous article, Many Roads, October]

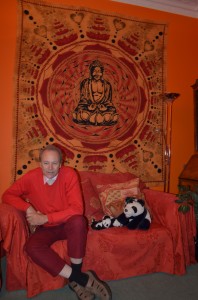

He is staying at the Panda Villa guest house in Kilmaurs Road, Edinburgh. Everybody in my Buddhist Thinkers’ Group has heard of David except me.

My curiosity aroused, I phone David and make an arrangement to meet him the following evening. On the phone he sounds welcoming and I look forward to our meeting.

The Panda Villa is an unusual abode, as far as guest houses go – a Buddhist-themed gem of a place. The hallway walls are painted maroon and hung with various paintings and photographs. David is in the sitting room looking relaxed and somewhat avuncular on a sofa in front of an enormous cloth print of the sitting Buddha. The building is Victorian and the room in which we meet has a high ceiling and an elaborate cornice. On the sofa, alongside David, is a stuffed panda with its cubs. I’m told the owner, Martin, had something to do with the preservation of pandas before opening his guest house.

I ask David about his latest book, Not Everything is Impermanent. He tells me the idea came about through a group of his students who were interested in collecting together his shorter writings. The original idea was to publish separate themed booklets, the writing gleaned from his blog posts and ideas he had written about as short pieces on his web site.

When they had collected his writing, he tells me, they thought, Actually, there’s quite a bit of stuff here, so why don’t we just stick it all together and make a book, rather than little booklets? David finished the work by editing the document and smoothing the rough corners. And this is how the book came about.

It’s the type of book you can dip into anywhere at random, David says, unlike his other books, which have a theme running through them and have to be read from beginning to end to make sense of them.

Zen Therapy is the book that is mostly associated with David; being the name of the Zen Therapy Institute, he says, It’s become a kind of trademark. The Institute runs courses in Korea with online and attendance components. Two years of study are required with a certain number of hours dedicated to attendance in Korea which is then combined with the online course.

Some people just do the online course. They can do that programme without attending anything, he says.

David spends each August in Korea to oversee public lectures and events on the course. Because of the distance, attendance at the course is not ideal. He had considered running four ten-day courses a year but the expenses incurred by the air fares would be prohibitive.

In Peru they have an existential psychotherapy institute. One of their divisions is a Zen therapy group. I teach on about half of the courses that they offer and then they buy in other trainers to do other units, David tells me. David will be going over before Christmas to do a week’s teaching in Peru and then a week in Chile. I find it a little difficult to imagine Buddhism in those countries. David assures me, If it was straight Buddhism, you’re probably right. There are lots of people interested in Buddhist psychology and therapy and then there are lots of people interested in psychology, personal growth, all that sort of thing. This provides you with a vehicle. It means that some people are Buddhist and want to do Buddhist things. Most people are just interested in personal growth or in their personal development as therapists.

David thinks that the likes of counselors and social workers view the Buddhist aspect as being kind of exotic. But David is seeing Buddhism in the context of a kind of psychology. You get all the literature, the abhidharma about the conditioning of the mind. I’ve done quite a bit of work on it, translating that into a form that westerns can make use of, modern people can understand and see. A lot of the Buddhist ways of doing things was sort of to try and produce an almost periodic table of states of the mind. But that doesn’t appeal very much to westerners. Most of the categories do have an implicit, functional equivalent where western psychologists are interested in a functional approach.

Whether the Buddhist aspect of psychology anticipates or contradicts the way in which psychologists interpret states of mind leads David to think of how, in fact, a particular way of thinking about mental states might lead to actually helping people.

I ask him about archetypes and if they exist in any form in Buddhist psychology.

Archetypes, he says, are a western idea, a language, a way of talking about some of the tings that Buddhism talks about in another language. Archetypes, David views as being quite helpful as they allow people to be able to access spiritual matters without feeling they are being too religious. A lot of modern people, especially this side of the Atlantic, are allergic to whatever they think is religious. They need to be provided with some way of coming to terms with the stuff without thinking they’re labeling themselves in some way. Archetypal language is one way of doing this.

David defines meditation as the mind contemplating a wholesome object, although he admits that the definition of a wholesome object might be difficult to understand. For a Buddhist, the most wholesome thing would be the Buddha. Contemplating the Buddha is top of the list of many Buddhist meditation manuals.

This is fine for a Buddhist, David thinks, but this doesn’t work for someone who is secular. So then, you’ve go to make some transposition – what would be a Buddha for them? And the Buddha in this sense is like the embodiment of love, compassion, wisdom, peace, these sorts of things that everybody can relate to.

During his visit to Edinburgh, David was invited to a prison by a Christian chaplain, the service having an obligation to cover all faiths. Some of the prisoners had signed up to a meeting. I had a little group and we had a very nice, sensitive group encounter. I’d not done it in a prison in this country before but I had done it, quite a number of years back in a prison in Florida and then a somewhat different programme in another prison in California. I think if you’re working with people who’ve hit bottom, although they are defensive in certain ways, they’re open in some other ways that the ordinary person maybe isn’t.

Having discussed the identity theory in a recent University of the Third Age Group, I wondered what David thought about the relationship between the mind and the body. You have the notion of the bardo state: but even in the bardo there has to be a form of some kind. It may not be a material form It’s to do with ontological status of that which is primarily spiritual. Of course, this is one of the things that Shakyamuni Buddha staunchly refused to pronounce about. We’ve been left with this philosophical vacuum which many different schools of Buddhism have been very happy to fill in one way or another.

I leave David in the hallway. He maintains his relaxed mood and he accepts an invitation to dinner the following evening. Although he is extremely busy with his writing and his workshops, I get the impression that he still gives priority time for personal meetings and communication.

Sourced from chapters in Not Everything is Impermanent

To Enter One Must Become Foolish

“The description of spirituality requires a vehicle or language, a system of concepts and ideas, but these always fall short. Hence simplicity seems complex and straight-forwardness paradoxical. Words can make a map, they are not the territory. Not even a map, they are signposts…”

The Ultimate is Also the Proximate

“The fact that only unmeasurable things exist means that ordinary things actually partake of exactly the same mystery as ultimate and infinite ones…This is one meaning of the Buddhist teaching of shunyata, the “emptiness” of things. Although we try to catch things in our net of measurement, the real things always slip away through the holes in our system.”

We Cannot Help Intuitions of Wholeness

“…being the creatures that we are, we cannot help attributing names to the unnameable. In the contemporary age we have access to many great spiritual traditions and in each of them we find names for the unnameable. This is good. It shows that this vital intuition is not just the clever invention or property of one group of people. It is a universal phenomenon. Humans intuit the infinite from the finite, the ultimate from the proximate, the sublime from the ordinary. We are spiritual beings through and through and we do not need to limit ourselves by cutting off our most important intuitions or building a wall of taboo against thinking of greater things.”

From David Brazier’s weblog http://amidatrust.typepad.com/dharmavidya/

See also Address to the Scottish Parliament and Interview on mindfulness with the BBC, 09/12/2014 from 01:41:22

Leave a Reply